About

Data for Justice

How can we develop safer and more responsible artificial intelligence (AI)

in the public sector? The solution appears to lie in multi-sector

collaboration. Since July 2022, a partnership involving the German

Consulate in Rio de Janeiro, the Rio de Janeiro Public Defender’s Office

(DPRJ), various civil society organizations, and ITS has created a secure

environment to develop more inclusive AI.

Using judicial data, a pilot project was launched to enhance the DPRJ’s

work on healthcare access. In nearly 20 years of operation, public

defenders in Brazil have achieved significant successes in guaranteeing

health rights. However, the institution remains constrained by limited

human resources: there is currently just one public defender for every

150,000 people. Despite Brazil’s robust legal framework for health rights

and its universal healthcare system, medication denial cases rise by

about 5% annually, with at least 500,000 cases still pending. Moreover,

59% of the population is eligible for legal assistance and guidance.

The citizens served by public defenders are among the most vulnerable

and marginalized. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, where the project took

place, 81% of those assisted by the DPRJ earn no more than one

minimum wage. Additionally, cases related to medication denial in Rio de

Janeiro alone surpass 100 per month, occasionally peaking at 10,000

cases monthly.

Brazil, which holds the world’s largest digital repository of legal data, has

long used data to improve its justice system. Public defenders are

pioneers in developing innovation teams to leverage digital tools effectively. The application of machine learning techniques can

significantly enhance the analysis of judicial data, providing valuable

insights and increasing efficiency — even when the AI used is simple and

accessible. This was a key conclusion of the project.

Building on this insight, the project focused on analyzing health litigation

data involving the most vulnerable groups. Using the AI Operational

Sandbox methodology — designed to ensure safe and responsible

technology development — the initiative began by forming a Multi-

Sectoral Committee. This committee incorporated diverse perspectives to

create an inclusive AI tool grounded in ethical principles and guidelines.

The report below presents the outcomes of this collaborative process,

offering a potential AI development model for the Brazilian public sector.

It draws on the experience of the AI Operational Sandbox at the DPRJ and

shares lessons on building ethical and responsible AI. The step-by-step

approach outlined in the case study, developed with input from DPRJ

staff, provides insights that may enhance the realization of the right to

health in Rio de Janeiro.

1. Data available

at: https://www.defensoria.rj.def.br/noticia/detalhes/20377-Historias-do-

Plantao-Noturno-defesa-do-direito-a-saude-e-destaque e

https://www.defensoria.rj.def.br/uploads/arquivos/09d3bcf2aa2c44e28f

b55498d0a65f3d.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2023.

2. ITS report on these initiatives available

at: https://itsrio.org/en/publicacoes/the-future-of-ai-in-the-brazilian-

judicial-system/. Accessed March 20, 2023.

research

To build ethical and responsible AI, the Operational AI Sandbox aimed to

ensure that various sectors of society potentially affected by the

technology were represented. The project involved diverse stakeholders,

including academia, civil society, and technical staff. Social participation

in technology projects promotes the formation of multisectoral groups

that contribute to establishing values and principles aligned with human

rights and fundamental freedoms, particularly the rights of marginalized

and vulnerable populations.

The Multistakeholder Committee supported the collaborative design of AI

technology using a test platform within the Operational Sandbox. The

Committee included experts from the DPRJ, the NGOs PretaLab and the

Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS), the Fiocruz Institute, the Sérgio

Arouca National School of Public Health, and members of the technology

development sector.

The Committee’s experts defined the development roadmap and the

mechanisms to be institutionalized in the technological tool, while also

establishing and validating the Sandbox principles for responsible

development. The diversity of knowledge and experience among

members was invaluable to the project’s design and implementation.

results

Diagnosis of Health Litigation Data in Rio de Janeiro

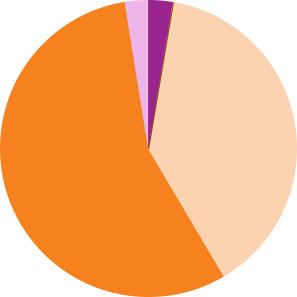

The dashboard below provides structured visualizations of the primary

litigants and the regions generating the majority of health litigation cases

in Rio de Janeiro. Monitoring activities included screening a list of 7,000

medications and identifying their presence in cases handled by public

defenders in the state.

Through discussions held by the Multistakeholder Committee, the

following were defined: (1) Key questions to address in developing the

technological tool; (2) Ethical and political parameters for the tool’s

development; and (3) Desirable requirements for the tool’s safe

implementation.

Based on these definitions, a diagnosis was conducted using the health

litigation database provided by the DPRJ. This involved accessing the

DPRJ’s Verde system database, from which 13,812 entries were

extracted, covering actors (plaintiffs, defendants, etc.) involved in

lawsuits related to medications and treatments.

An exploratory analysis followed, identifying the questions that could be

addressed with the current database and determining potential

improvements to the database structure to answer additional questions.

Finally, a code was developed to prototype a solution addressing a

selected key question.

The primary questions defined by the Multistakeholder Committee to

guide the project were: What is the profile of the defendant? Is it a public

or private entity?

Understanding the profile of defendants can facilitate informed decision-

making, which is crucial for state-wide public health policies. For instance,

data insights can reveal whether the Unified Health System (SUS) is being

more or less utilized by the population. Additionally, answering this

question equips public defenders with a comprehensive understanding of

health litigation in Rio de Janeiro, enabling them to pursue more efficient

and strategic legal action.

3.1 Consistency

To conduct statistical studies, it is essential to ensure that the data in the

database accurately represents the modeled reality. This is achieved by

identifying any violations of integrity constraints, which indicate

discrepancies between the data model and reality. Therefore, analyzing

data consistency within the system is a critical step. The conclusions

drawn from this analysis also help establish the reliability of the database

for future AI projects.

An analysis of the data consistency in the Verde system revealed no

violations of integrity constraints. The Foreign Key (FK) and Primary Key

(PK) relationships between database tables were found to be consistent,

enabling the desired and feasible cross-referencing of data.

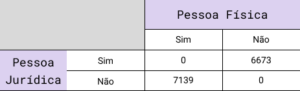

Additionally, a second consistency validation was conducted to check for

overlapping information between the natural person and legal person

tables. The results, shown in the table below, confirm that no overlaps

exist — meaning no database entry simultaneously represents both an

individual and a legal entity.

3.2 Additional Cross-Checks

To better understand the profile of defendants — specifically whether they

are public or private entities — several characterization cross-checks were

performed, as detailed in this section.

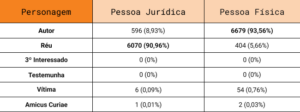

First, the profiles of natural persons and legal entities were identified, as

shown in the table below. The data indicates that the majority of

plaintiffs are natural persons while the majority of defendants are legal

entities. This aligns with the expected proportion, given the nature of the

cases: in most health-related litigation, a natural person (the plaintiff) files

a case against a public or private legal entity (the defendant).

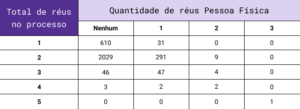

The data also shows that some cases involve multiple defendants, with

variations in the types of defendants (individuals or companies). Given

this, an analysis of the number of defendants per case was conducted.

This analysis helps public defenders determine how to best target their

legal strategies.

The table below shows the distribution of defendants across cases. The

rows represent the total number of defendants, while the columns

indicate the number of individual defendants. The “None” column shows

cases where no individual defendants are present. The remaining

columns display cases with one to three natural person defendants. Of

the 6,070 cases involving at least one legal entity as a defendant, only 356

cases (5.86%) also include at least one natural person defendant.

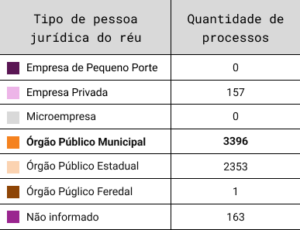

An additional analysis was performed in 5,097 cases with at least one

legal entity as a defendant. The table below categorizes these cases by

the type of legal entity involved. *

The data reveals that over 97% of defendants are public bodies, with

more than 50% being municipal entities. This outcome aligns with

expectations, given the focus on health-related cases and Brazil’s

decentralized public healthcare system (SUS). In the SUS, responsibilities

are shared across federal, state, and municipal levels, with municipalities

typically tasked with service delivery within their territories.

4. Relevance of Data Cross-Referencing

The project yielded significant results and valuable insights, such as the

challenge of converting structured PDF text into raw text data. The tables

presented offer structured visualizations of the primary litigants involved.

These results aim to strengthen public defenders’ ongoing efforts to

expand health rights for vulnerable groups in Brazil. The project focused

on developing and transferring open-source AI technology, leveraging

judicial data provided by the DPRJ to enhance the reach and efficiency of

protecting access to medications for marginalized and vulnerable

populations.

For a comprehensive understanding of the project’s development,

challenges, and outcomes, we recommend accessing the Toolkit, which

details the project’s objectives, methodology, challenges, and results.

* It is possible for a case to involve multiple defendants (individuals or

legal entities), and different types of legal entities may be present in the

same case. Therefore, the table does not represent unique occurrences;

for example, if a case includes both a Private Company and a Municipal

Public Body as defendants, it will be counted in both corresponding rows.